JARASH – If you ask him where he would like to live, Khalil will tell you: “The city of Tulkarem”. It takes a while to discover that the city of his dreams, the city where for the first time in his life he would not feel like a refugee, is a place he has never seen. Only his parents knew this city.

Khalil Hadi Ali Muthili left Gaza city when he was 12 years old, in December 1967, after the second Arab-Israeli war – the “Six-Day War”. On his day of departure, he can remember that the skies had opened and heavy rain was pouring down on the people dragging their few belongings away from war in search of a new life. They were the sons of refugees, and they were to become the fathers of other refugees. In 1948, after the first Arab-Israeli war, Khalil’s parents had left the West Bank town of Tulkarem and found refuge in Gaza. Now, twenty years later, the whole family was on the move again. First they stayed in Ramallah for a few days, before moving on to the Jordan valley where they spent four months. Then, like tens of thousands of others, they moved to Jordan to a temporary camp. Finally they made it to Jerash refugee camp, some 60 km north of Amman. This settlement of 1,500 tents hosting 11,000 Palestinians on the run, was to become an agglomeration of concrete where 27,000 people – mostly refugees from Gaza – are still crammed today. “We left everything behind, our land, our jobs. We brought nothing with us from Gaza, just as my parents had brought nothing with them from Tulkarem. Our family lost everything twice; we don’t even have a picture to hang on to. We only have our memories”.

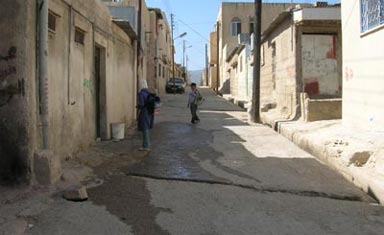

In the camp, winters were harsh, and the summers unbearable. As it became clear that there would be no speedy return home, the tents were slowly replaced with concrete shelters. Khalil wanted to maje something of his life. He was stubborn, and smart. In the camp, he attended the UNRWA school and was able to complete his studies. He became a teacher, but couldn’t find a job in Jordan and had to move to Saudi Arabia for 15 years. His wife moved with him. They had five children, and they established a family. Then, in a bitter turn of fate, he became sick and had to return to Jerash. With the savings from Saudi Arabia he was able to buy an unhealthy but cheap shelter in the camp. His wife found a job in a factory, but she also became ill. Today she is still in hospital, not knowing when she can leave – and Khalil cannot even stand up without help. His oldest son is 17, and his youngest has just turned one. The family lives from public or private subsidies. “I went through many difficult moments in my life, but the hardest time was when I came back from Saudi Arabia, sick and jobless: I just didn’t know where to turn to for help”.

Khalil applied for assistance from the UNRWA relief department, and was registered as special hardship case. In 2006, ECHO included him as one of the beneficiaries of their shelter-rehabilitation project, implemented by UNRWA. Between 2000 and 2007, ECHO has funded the reconstruction of 70 shelters in Jerash camp benefiting several hundred people. The Hadi Ali Muthili family shared two rooms with a leaking roof and almost no access to daylight. Once the work was completed, the sewage system no longer overflowed into Khalil’s kitchen on rainy days; the zinc roof was replaced and made watertight; and three rooms and a toilet were reconstructed. The family had light, ventilation and privacy. It was a great help, but their problems are still far from solved. In Jerash camp unemployment and poverty are very high, and work opportunities are mostly in the casual sector.

Meeting the vital and basic needs of the most destitute is therefore not enough. In addition to its humanitarian intervention, the Commission decided that it was time to tackle the longer-term developmental and social needs of ex-Gaza Palestinian refugees to contribute to poverty alleviation and the improvement of living conditions. A new four-year project began in 2006. It included further shelter rehabilitation and support for special hardship cases like Khalil’s, but also the provision of basic social services like health and education, and the promotion of economic activities. Unfortunately it is likely to take some time before the positive effects of this new EC intervention are felt by ordinary people like Khalil and his family.

“Since I’m originally from the Gaza Strip, I don’t have full Jordanian citizenship – he explains. “We ex-Gaza refugees, do not enjoy full rights such as voting, working for the government, and benefiting from government services or licenses. We have difficulty establishing our own small businesses, and pay higher tuition fees for educating our children. My son is good at school. He has good grades and would like to study medicine. But I don’t know how I can pay for his studies. I’m really afraid he will end up stuck here, in this camp, without a real life, without a professional future. Education is the most important thing, but I’m afraid I won’t be able to provide it for my children…”

In the meantime, they play in the mud, next to an open sewage system. They are the children of Jerash camp: the third generation of refugees, in what is the longest exile in modern history.

Daniela Cavini

ECHO Regional Information Officer – Amman